Fascinated as I was with the 1960s when I was younger I spent the better part of my college years studying social change movements. From the Civil Rights movement to the anti-Vietnam War movement, these schools of thought and marches and gatherings caused significant upheaval. While they weren’t as born of impulse or altruism and while they didn’t leave as big a mark on American culture as their proponents would have us believe, these movements did for better or worse make change. They also made it seem in retrospect as if there wasn’t much left for future generations to change. This is part of what makes looking at the Occupy movements happening in the U.S. and around the globe so hard for me to get my head around.

First, let’s talk about Occupy as a banner heading. I get it. The protestors are using the oldest confrontation tactic in the book: show up and don’t go away. But I have a real philosophical problem with the concept of “occupation” as a viable populist movement. Occupation implies that those being occupied are the rightful owners or dwellers or possessors of what is being occupied. Indeed, one commentator I heard on MSNBC several weeks ago remarked that Wall Street is from a Native American perspective already occupied. While I think this complaint stretches too far back too specifically into history to be legitimate as stated it does make a valid point about how the widening wealth gap in America disproportionately affects Native Americans, African Americans, Latinos, and other minorities. It also sharpens the focus on part of the problem I have with the Occupy movement.

Occupation as the name for what the philosophy, rather than the execution, of this movement legitimizes the idea that the bankers, hedge fund traders, and other denizens of the financial world who are largely the movement’s targets, have a right to act the way they’re acting. In fact, this movement should be stressing the opposite idea: that these bankers, traders, and financial manipulators actually owe the American people a public service debt. Propublica has a handy list of firms who took and returned bail out money. Sort it by the “Revenue to Gov’t” column to find out which firms gave money back.

Of the 926 firms that took bail out money from the U.S. Treasury 623 of them have paid zero dollars back. Admittedly, not all of the firms listed are in the financial sector (19 are classified as “State Housing Orgs” and 4 are classified in the “auto company” category), and some firms, like Bank of America, are listed twice: once as a bank and once as a mortgage servicer. When you eliminate the car companies and the state housing funds, which were set up to provide innovation to states hardest hit by the housing value crash you’re left with a staggering figure: 74%

Seventy-four percent of the companies that took U.S. taxpayers’ money to prop up their businesses or help inject life into the U.S. economy have paid back not one red cent. And since the U.S. economy is really no better off than it was when the bail out money was paid out to those firms it’s clear that the implied mandate of those loans wasn’t fulfilled, unless, of course, you count paying out millions of dollars in bonuses to investment bank staff.

Based on the interest free use of taxpayer money doesn’t logic dictate that those occupying Wall Street aren’t really usurpers but are instead the rightful owners of those firms’ outputs and profits?

It seems like a simplistic take but it’s also an approach that in all the coverage I’ve read of the Occupy movement, both progressive and conservative, no one has seemed to bring up.

The other thing that makes it so hard for me to get my head around the Occupy movement is not the fact that they don’t have a coherent set of goals and demands. I kind of like the fact that the movement is inchoate even a month later. No, what makes it so hard for me to get my head around Occupy is that it’s happening in my adult life.

I look at the movement, one I don’t have the leeway to participate in because for better or worse I am employed full time (and yes, I realize even as much as I hate my job how brilliantly lucky this makes me at this point), and I have to wonder if this is how my grandmother felt looking at the anti-Vietnam War protests on TV and in the streets. She was 58 in 1968, still working full-time, with the last one just about to leave the nest. I know she didn’t support the war; we talked about it years later when I was in college. And I know she wasn’t stupid so she understood both the deeper political reasons why U.S. involvement in Vietnam was a bad idea as much as she understood the often more intimately personal reasonsfor opposing the war. But did she feel this same sense of treading water, of anticipation for something she could do or some way she could get involved that I do with Occupy? Likely not. My grandmother was of her time in much the same way I’m of mine.

Since I’m not in a position to go camp in McPherson Square, and since I don’t agree with everything the Occupy seems to want, the only thing I can do is promote some of the events and activities I think make sense.

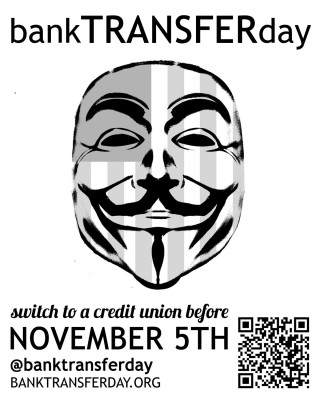

Bank Transfer Day or the Move Your Money Project aren’t an “official” Occupy events. There are no official Occupy events per se. At least, I don’t think there are, but as a grassroots activity this one I like.

The folks promoting Bank Transfer Day and Move Your Money urge people to take their money out of large financial institutions like Bank of America, Chase, and Citibank and deposit it in local or regional banks or in credit unions. To me this is the ultimate power of capitalism at its best: the consumer doesn’t like the way these large banks are doing business so the consumer is going to take her business elsewhere.

To me Bank Transfer Day and Move Your Money are little bit like Buy Nothing Day. They force me to think about the companies with which I am doing business.